This story was published in print for the May 29 issue of Parc-Extension News. Some information may have changed.

Avleen K Mokha

Over the last month, the number of cases have risen in the Villeray—Saint-Michel—Park-Extension (VSP) borough. With cases nearing 2,000, COVID-19 is evidently affecting residents. But why is the VSP borough hit so hard? And what does it mean for Park Extension specifically?

A look at numbers

So far, Villeray-Saint-Michel-Park-Extension has 1,747 cases of COVID-19. The disease has killed 111 residents of the borough.

While this total number is related to major outbreaks in senior care facilities like CHSLD Saint-Michel, looking at the most recent data on Park Extension shows a worrisome rise in community cases.

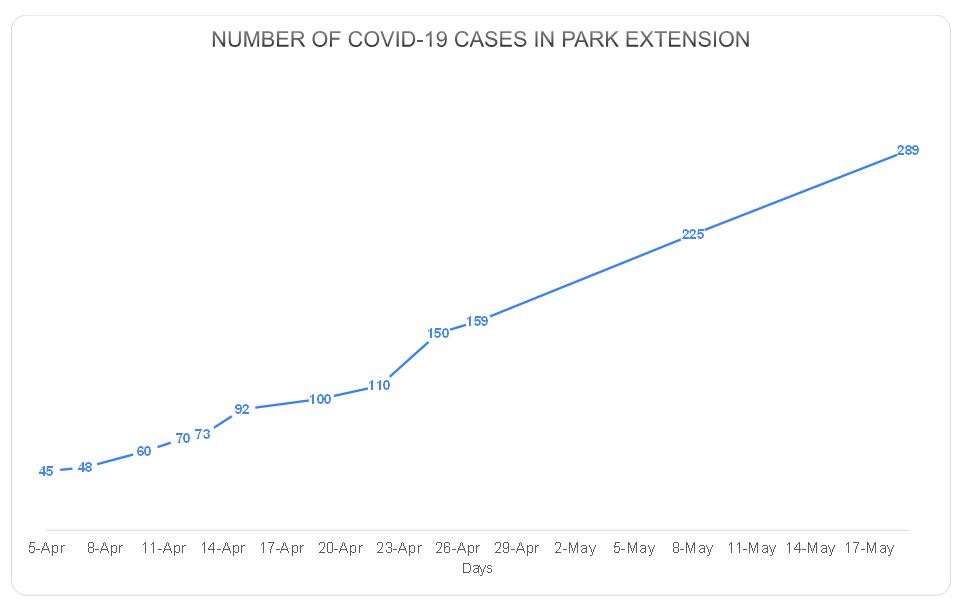

Documents from CIUSSS West Central show that Park Extension had 45 cases at the start of April. By April end, 159 cases were confirmed. The district saw an increase in May, with 289 cases confirmed on Tuesday, May 19. May 19 was the first day of the testing clinic outside Parc metro, so we can expect an increase in the coming days.

The story numbers tell

But numbers are only the beginning of the story. Park Extension has underlying issues in common with other high-risk districts, like poor housing and working conditions.

Fo Niemi, director of Montreal’s Center for Research-Action on Race Relations, told the Gazette that the majority of residents in the Côte-des-Neiges hotspot are renters, with many living below the poverty line. American studies suggest a direct link between low-income communities and vulnerability to disease outbreaks, due in part to housing density and poorer health.

Park Extension has a significant renter population – 79%, according to the 2016 Canadian census. More than a third of Park Extension is made of low-income residents, including new immigrants and single-parent families.

Having a lower income puts pressure to keep working during the pandemic, which makes it important to consider working conditions.

Poor working conditions

If you catch it at work, you can pass it to your neighbour. The risk of getting the virus at work may be higher for residents working long hours in spaces where a 2-meter distance can’t be maintained, or where masks and gloves are low in supply. For instance, Saint-Michel became a hotspot partly because of a high number of healthcare workers who tested positive.

Park Extension includes migrant workers and students that work essential jobs at-risk of outbreaks, such as packaging food. Already a Cargill meat-processing plant south of Montreal shut down after at least 66 employees got COVID-19.

Up north, one employee died and 24 tested positive at a Maple Leaf Foods plant. Workers at this plant were not unionized, which may limit their ability to advocate for better rights.

Need for effort which suits the community

Quebec has slowly reached its goal to ramp up tests. Mobile testing clinics, like the one set up by Parc metro, will give much needed data to health officials.

But Park Extension needs more than a plan to increase testing. Park Extension needs reformed action which accounts for the realities of its people.

This week, the bus clinic’s hours were cut short to 2 pm on Tuesday and Wednesday. But most workers couldn’t make it even the week of May 19, when the clinic stopped people from lining up by 3:45 so it could close by 4 pm.

Andrés Fontecilla, district representative at the Quebec National Assembly, echoes these concerns.

“The clinic should stay open until at least 8 PM and be open on the weekends,” Fontecilla said in a social media post. “The success of this testing operation lays on the possibility of testing as many people as possible, including people who have to work outside the neighbourhood.”

Trouble with the clinic also came when the testing site changed before the clinic’s first visit. Borough councillor Mary Deros says the fight to relocate from a dead-end on Saint-Roch to an accessible location took a week

Why was a dead-end the first testing site for a low-income neighbourhood, with crowded housing and poor working conditions, to test for a virus that spreads through social contact?

CIUSSS West Central spokesperson Jennifer Timmons says, “The exact location and hours of the clinics are subject to change at any time.”

Residents tell Parc-Extension News that the main ways they heard about the testing clinic was through word-of-mouth, or through translated materials made by community volunteers.

These communication modes don’t work if essential information like dates, times, and location, change because of push-and-pull among officials. Changes may not reach the people who need to hear it the most, like seniors living alone, who depend on family or community members for translating official guidelines.

One way out of the communication issue is to set up a permanent testing site with regular hours, which the borough has done in Saint-Michel. Unless efforts match the community’s reality soon, officials may be playing a waiting game with a deadly illness.

A version of this story was published in the May 29 print issue for Parc-Extension News. Click here to read the full issue.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors in Opinion & Editorial are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.